I wrote about Remedios Varo for my newsletter: https://open.substack.com/pub/sabinastent/p/vampiros-vegetarianos?r=ceu&utm_medium=ios

I wrote about Remedios Varo for my newsletter: https://open.substack.com/pub/sabinastent/p/vampiros-vegetarianos?r=ceu&utm_medium=ios

In other news, I am thrilled to appear on the pilot episode of “Branched Out” – possibly “the world’s first ever podcast to unearth the deep-rooted interconnections between multicultural and LGBTQ-inclusive stories and trees” – speaking about Frida Kahlo’s “Tree of Hope” (which I wrote about a couple of months ago on my Substack). Available on all your favourite podcast providers!

A love letter to his wife Marilyn Monroe. That was Arthur Miller’s intention behind The Misfits: a role to finally distance Monroe from her bombshell image and establish her as a serious actor. Instead the John Huston directed picture, based in the Nevada desert, is as much about death as it is about freedom. Clark Gable, cast as aged cowboy Gay, died shortly after the film was completed. We have Monroe playing nervous young divorcee Roslyn, shaking uncontrollably – more so than was required of her character – the black and white production could not conceal her poor skin, mental decline and physical health. She would be dead a few months later. For Montgomery Clift, as rodeo rider Perce, the role came five years after the horrendous car crash that scarred his once perfect features. It would be one of his final roles and Clift would be dead five years later, never having fully mentally recovered from the accident and the emotional turmoil caused by this disfigurement. The scars of his past haunt his character through the line of dialogue: “my face is fine. It’s all healed up. It’s just as good as new”. In him Monroe found a kindred spirit, admitting in a 1961 interview that he was “the only person I know who is in even worse shape than I am.” Heartbreaking.

When recently divorced Roslyn and her older friend (peerless Thelma Ritter) catch the eyes of ageing cowboy Gay and his friend Guido (Eli Wallach) in a bar they sidle over to their table. Soon they are inviting the women to Guido’s abandoned home, unfinished since his wife’s death, in the Nevada desert. The young woman and the older cowboy immediately become a couple – setting up home, fixing the ramshackle house and planting lettuce in the garden. Roslyn’s intense affection for all creatures – Gay’s dog, the rabbit Gay threatens to kill for eating their crops – is constantly on display, yet this part of her is shot-down for being soft and silly. They set off Mustanging – rounding up wild horses – and pick up Perce from the rodeo on their the way. In the Nevada desert we have an expanse of land that is as dry and cracked as a failed marriage, echoing with the emotional and physical scars of childless couples, deceased partners and love affairs been and gone. The expanse is as much about Miller and Monroe’s dry relationship as it is about the industry. When Perce tells Roslyn, “I don’t like to see the way they grind up women out here,” he could have been referring to Hollywood’s ability to spit out once lauded stars.

The whole mythology of The Misfits is grounded in its stars and a deep yearning for both happiness and freedom. All of the characters talk of liberation but they are the ones snatching it away from one another, and rounding up these free animals when they desire it from them the most. It is a phenomenal film with an explicable link to the industry, Hollywood history and forever entwined in the mythology of its stars. They are those Misfit horses who have been captured and lassoed, but in their legacies, in memory, they run eternally wild and free.

* This post originally appeared on my now defunct old blog, 10 June 2015.

David Lynch once described living near Mulholland Drive: “At night, you ride on the top of the world,” he said. “In the daytime you ride on top of the world, too, but it’s mysterious, and there’s a hair of fear because it goes into remote areas. You feel the history of Hollywood in that road.”

Mulholland Drive is Lynch’s gorgeous Surrealist neo-noir, a mysterious fable about women, memory, identity, and Hollywood; a town built for movies and stardom but where illusions are shattered. The film works well as a double-bill with Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard (1950), a road we see at the beginning of the film. At the 2001 press conference for Mulholland Drive, Lynch described the “human putrefaction” – the decay and corruption of humanity, especially in the Los Angeles film industry – within a city of “lethal illusions.” He believed that Wilder saw this condition and was equally fascinated by it, too.

In Mulholland Drive, the lives of Betty (Naomi Watts) – “I came to L.A. to be a movie star” – and amnesiac Rita (Laura Harring), who has escaped a fatal car crash on the winding hills of Mulholland Drive, merge and collide. Both actors were cast purely by their photographs, and Lynch had not seen any of their previous work. Harring was involved in a minor car accident on the way to the first interview, something she considered an act of fate after learning her character would also be involved in an automobile collision. Watts based her portrayal of the wholesome Betty on various Hollywood blondes, including Doris Day, Tippi Hedren and Kim Novak. She described Betty as a thrill-seeker, someone “who finds herself in a world she doesn’t belong in and is ready to take on a new identity, even if it’s somebody else’s.”

Michael Wilmington of the Chicago Tribune said, “everything in Mulholland Drive is a nightmare. It’s a portrayal of the Hollywood golden dream turning rancid, curdling into a poisonous stew of hatred, envy, sleazy compromise and soul-killing failure.” Watts said her early experiences in Hollywood paralleled those of Diane’s (again, Watts in a dual role). Plus, she had her own history with the stretch: “I remember driving along the street many times sobbing my heart out in my car, going, ‘What am I doing here?’” she once said.

Mulholland Drive originated as a television pilot, and Lynch filmed the open-ended scenes in 1999. However, after television studios rejected the show, Lynch conceived an ending. Some audiences felt the effect, a part-show, part-film hybrid, lacked the cohesion of Twin Peaks (clearly a T.V. series; The Return, ironically, is considered a film) or Blue Velvet (a movie).

As the Guardian’s film editor Michael Pulver wrote in his recent David Lynch tribute:

“Initially it [Mulholland Drive] appeared to go disastrously wrong, as Lynch had pitched it as a Twin Peaks-style TV series. A pilot was shot and then cancelled by TV network ABC. But the material was picked up by French company StudioCanal, who gave him the money to refashion it as a feature film. A noir-style mystery drama, it was another big critical success, secured Lynch a third best director Oscar nomination and in 2016 was voted the best film of the 21st century.”

Like most – if not all – of Lynch’s work, Mulholland Drive is open to dream analysis, especially given the film’s tagline of “love story in the city of dreams.” But it is also one of Lynch’s most linear films. One interpretation is that the real Diane Selwyn has cast her dream self as the sweet and optimistic Betty Elms, rewriting her past and self into her version of an old Hollywood film. This would fit in with some additional elements, including the casting of Ann Miller as Coco (an Old Hollywood star in her final film role), who represents the golden age of movies.

But in the film’s second half, the dreamer is woken up, and the illusion is shattered as the characters wake up to find themselves in Los Angeles purgatory. Watts had her own explanation of the film, which was closer to what many viewers believe to be true. As she said, “I thought Diane was the real character and that Betty was the person she wanted to be and had dreamed up. Rita is the damsel in distress and she’s in absolute need of Betty, and Betty controls her as if she were a doll. Rita is Betty’s fantasy of who she wants Camilla [Harring in a dual role] to be.”

Harring, meanwhile, said, “When I saw it [Mulholland Drive] the first time, I thought it was the story of Hollywood dreams, illusion, and obsession. It touches on the idea that nothing is quite as it seems, especially the idea of being a Hollywood movie star. The second and third times I saw it, I thought it dealt with identity. Do we know who we are? And then I kept seeing different things in it…”

Mulholland Drive is a film where your opinion may change with every viewing, which is what makes every watch of the film so richly rewarding. What is real, what is the dream, and what’s the nightmare? I will leave you with a quote from The Cowboy, who I believe has one of the film’s most appropriate lines: “Hey, pretty girl. Time to wake up.”

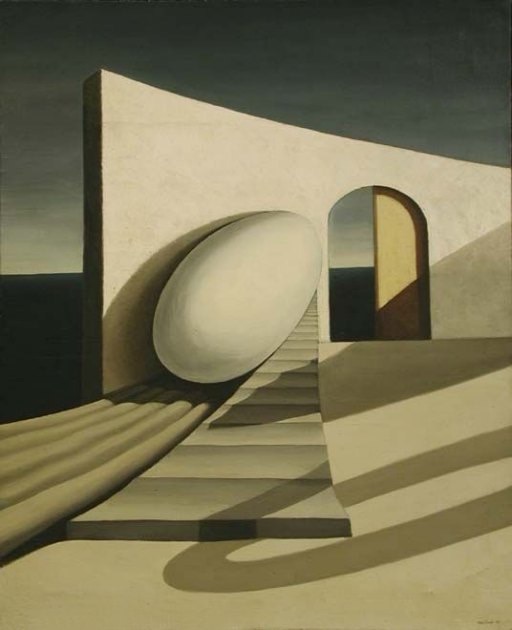

For Easter, more Kay Sage:

https://open.substack.com/pub/sabinastent/p/my-room-has-two-doors?r=ceu&utm_medium=ios

In her August 1997 BFI piece “Voodoo Road,” the historian Marina Warner wrote, “the plot of Lost Highway binds time’s arrow into time’s loop, forcing Euclidian [sic] space into Einsteinian curves where events lapse and pulse at different rates and everything might return eternally.” She continues, “But this linearity is all illusion, almost buoyantly ironic, for you can enter the story at any point and the straight road you’re travelling down will unaccountably turn back on itself and bring you back to where you started.”

Lost Highway, David Lynch’s seventh feature film and his first after Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me, has all the markings of a quintessential LA film noir, but with a Lynchian nightmare spin. It’s a Moebius strip of a movie: multiple plots loop around and on themselves, and storylines run along parallel lines but never fully link together for total resolution. The film takes its title from a phrase in the book “Night People” by Barry Gifford, who also wrote the literary version of “Wild at Heart.” However, rather than adapting the source material, Lynch and Gifford decided to base the film on videotapes and a couple in crisis.

As Lynch detailed in his autobiography “Room to Dream”:

“Another beginning idea was based on something that happened to me. The doorbell at my house was hooked to the phone, and one day it rang and somebody said, “Dick Laurent is dead.” I went running to the window to see who it was, but there was nobody there. I think whoever it was just went to the wrong house, but I never asked my neighbors if they knew a Dick Lau-rent, because I guess I didn’t really want to know.”

The result is a two-tale story: in the first, Jazz saxophonist Fred Madison (Bill Pullman) is fixated that his wife Renee (Patricia Arquette) is having an affair, and suddenly finds himself in prison, accused of her murder. In the second, you have the young mechanic Peter Dayton (Balthazar Getty) and the blonde temptress/ adulterous gangster’s moll, Alice. The only constant is Arquette in her dual roles, and, as Warner says at this middle point, “the film changes from an ominous Hitchcockian psycho-thriller to a semi-parodic gruesome gangster pic.” Arquette’s dual femme fatale roles also heighten the noir element, she is Uma Thurman-esque with her blunt brunette fringe, then Marilyn Monroe-like with her soft blonde waves. We also have the brunette/blonde dual role – or self – in Mulholland Drive.

The film’s casting is inspired. Robert Blake – who did not understand the script at all – is incredibly creepy as the sinister mystery man, his portentous appearance taking on a new significance since the Millennium. Best known as the 1970s television detective “Baretta,” in 2005 Blake was acquitted of murdering his then-wife Bonny Lee Bakley (following her murder in 2001). Richard Pryor appears in what was to be his final film role, and Robert Loggia. Loggia, previously annoyed about missing out on the role of Blue Velvet’s Frank Booth to Dennis Hopper, has an on-screen rant in Lost Highway that was unscripted and genuine.

Another LA-appropriate influence was O.J. Simpson, particularly his ability to return to regular life despite an infamous high-profile court case.

In her essay, “Funny How Secrets Travel: David Lynch’s Lost Highway,” the academic Alanna Thain writes, “David Lynch’s 1997 film Lost Highway is haunted by the specter of Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958), itself a ghost story on many levels.” Vertigo is a film about male obsession, aggression, and visual control, described as a deconstruction of the male construction of femininity and of masculinity itself. The critic James F. Maxfield suggested that Vertigo is an interpreted and variation on Ambrose Bierce’s 1890 short story “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge”, in which Scottie imagines the main narrative of the film as he dangles from a building at the end of the opening rooftop chase.

Thain continues, “Inspired by the spiral form that dominates Hitchcock’s masterpiece, Lost Highway explores the effects of living in a world characterized by paramnesia. A form of déjà vu, paramnesia is a disjunction of sensation and perception, in which one has the inescapable sense of having already lived a moment in time, of being a witness to one’s life.” In Lost Highway, did Fred murder his wife and then construct the rest of the outcome in a dream? And did that dream turn inwards into a nightmare?

These themes have appeared in Lynch’s other works, most recently Twin Peaks: The Return – Agent Cooper/Dougie, and that ending – in which characters are caught in a never-ending cycle of purgatory, dreams, nightmares, doppelgängers, and déjà vu. As the Mystery Man says, “We’ve met before, haven’t we?”

Lost Highway is an uneasy film and one of the most unsettling in terms of how deep it goes in terms of Lynch’s dream/nightmare logic. In “Room to Dream” Lynch wrote, “it’s not a funny film because it’s not a good highway these people are going down. I don’t believe all highways are lost, but there are plenty of places to get lost, and there’s some kind of pleasure in getting lost. Like Chet Baker said, let’s get lost.”

On that note, it’s time to get lost in Lost Highway.

I am thrilled to be hosting David Bradley in Q&A at Brum’s wonderful Mockingbird Cinema following the 6 pm screening of “Kes.” This Sunday, April 13th – a few tickets available, so snap ’em up!

https://mockingbirdcinema.com/MockingbirdCinema.dll/WhatsOn?f=501372