David Lynch once described living near Mulholland Drive: “At night, you ride on the top of the world,” he said. “In the daytime you ride on top of the world, too, but it’s mysterious, and there’s a hair of fear because it goes into remote areas. You feel the history of Hollywood in that road.”

Mulholland Drive is Lynch’s gorgeous Surrealist neo-noir, a mysterious fable about women, memory, identity, and Hollywood; a town built for movies and stardom but where illusions are shattered. The film works well as a double-bill with Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard (1950), a road we see at the beginning of the film. At the 2001 press conference for Mulholland Drive, Lynch described the “human putrefaction” – the decay and corruption of humanity, especially in the Los Angeles film industry – within a city of “lethal illusions.” He believed that Wilder saw this condition and was equally fascinated by it, too.

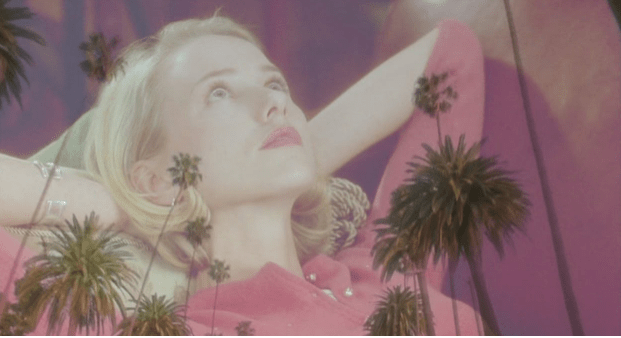

In Mulholland Drive, the lives of Betty (Naomi Watts) – “I came to L.A. to be a movie star” – and amnesiac Rita (Laura Harring), who has escaped a fatal car crash on the winding hills of Mulholland Drive, merge and collide. Both actors were cast purely by their photographs, and Lynch had not seen any of their previous work. Harring was involved in a minor car accident on the way to the first interview, something she considered an act of fate after learning her character would also be involved in an automobile collision. Watts based her portrayal of the wholesome Betty on various Hollywood blondes, including Doris Day, Tippi Hedren and Kim Novak. She described Betty as a thrill-seeker, someone “who finds herself in a world she doesn’t belong in and is ready to take on a new identity, even if it’s somebody else’s.”

Michael Wilmington of the Chicago Tribune said, “everything in Mulholland Drive is a nightmare. It’s a portrayal of the Hollywood golden dream turning rancid, curdling into a poisonous stew of hatred, envy, sleazy compromise and soul-killing failure.” Watts said her early experiences in Hollywood paralleled those of Diane’s (again, Watts in a dual role). Plus, she had her own history with the stretch: “I remember driving along the street many times sobbing my heart out in my car, going, ‘What am I doing here?’” she once said.

Mulholland Drive originated as a television pilot, and Lynch filmed the open-ended scenes in 1999. However, after television studios rejected the show, Lynch conceived an ending. Some audiences felt the effect, a part-show, part-film hybrid, lacked the cohesion of Twin Peaks (clearly a T.V. series; The Return, ironically, is considered a film) or Blue Velvet (a movie).

As the Guardian’s film editor Michael Pulver wrote in his recent David Lynch tribute:

“Initially it [Mulholland Drive] appeared to go disastrously wrong, as Lynch had pitched it as a Twin Peaks-style TV series. A pilot was shot and then cancelled by TV network ABC. But the material was picked up by French company StudioCanal, who gave him the money to refashion it as a feature film. A noir-style mystery drama, it was another big critical success, secured Lynch a third best director Oscar nomination and in 2016 was voted the best film of the 21st century.”

Like most – if not all – of Lynch’s work, Mulholland Drive is open to dream analysis, especially given the film’s tagline of “love story in the city of dreams.” But it is also one of Lynch’s most linear films. One interpretation is that the real Diane Selwyn has cast her dream self as the sweet and optimistic Betty Elms, rewriting her past and self into her version of an old Hollywood film. This would fit in with some additional elements, including the casting of Ann Miller as Coco (an Old Hollywood star in her final film role), who represents the golden age of movies.

But in the film’s second half, the dreamer is woken up, and the illusion is shattered as the characters wake up to find themselves in Los Angeles purgatory. Watts had her own explanation of the film, which was closer to what many viewers believe to be true. As she said, “I thought Diane was the real character and that Betty was the person she wanted to be and had dreamed up. Rita is the damsel in distress and she’s in absolute need of Betty, and Betty controls her as if she were a doll. Rita is Betty’s fantasy of who she wants Camilla [Harring in a dual role] to be.”

Harring, meanwhile, said, “When I saw it [Mulholland Drive] the first time, I thought it was the story of Hollywood dreams, illusion, and obsession. It touches on the idea that nothing is quite as it seems, especially the idea of being a Hollywood movie star. The second and third times I saw it, I thought it dealt with identity. Do we know who we are? And then I kept seeing different things in it…”

Mulholland Drive is a film where your opinion may change with every viewing, which is what makes every watch of the film so richly rewarding. What is real, what is the dream, and what’s the nightmare? I will leave you with a quote from The Cowboy, who I believe has one of the film’s most appropriate lines: “Hey, pretty girl. Time to wake up.”