Fortunately, somewhere between chance and mystery lies imagination, the only thing that protects our freedom, despite the fact that people keep trying to reduce it or kill it off altogether – Luis Buñuel.

Whatever art form it takes, whether painting, fashion, sculpture, or film, Surrealism has always been about disruption and the disorder of convention.

When the writer, poet, and co-founder of Surrealism André Breton was young, he and his friend, the French poet Jacques Vaché, would walk in and out of films at the cinema. At the end of the day, both young men would mentally edit all the images they had seen both on screen and off, mentally piecing the pictures together to create a personally unique movie of their very own. The result was ‘the visual collage thus put together in their heads as if it were a single film.’

We may say a similar approach was taken with Un Chien Andalou, Spanish filmmaker Luis Buñuel’s 1929 collaboration with Salvador Dalí. Both men pooled together two dreams, one each had experienced: Buñuel divulged his dream in which he saw a cloud sliced the moon in half, “like a razor blade slicing through an eye,” while Dalí replied with his dream about a hand festooned with crawling ants. These have become the best known images of Un Chien Andalou, a free association short film written by Buñuel and Dalí that continues to endure because of its Surrealist associations, Freudian symbolism, and dream imagery. The opening scene sets the tone, signposting the viewer to let the unconscious navigate. As Antonin Artaud once said, “the eye is the locus of transmission of meaning from writer to audience.”

Buñuel and Dalí intended their audiences to view the film in the same way as their artwork: reactionary, whether visceral or emotional. More importantly, they wanted audiences to suspend belief, let the unconscious take charge. The sliced eye was a metaphor that ‘links inner and outer, subjective, and objective,’ what author Fiona Bradley describes as a ‘glace sans tain’, or a mirror without silvering’. Suspend belief, go internally and let the subconscious take over. The sluiced eye would inspire the severed ear lying in the grass behind the white picket fence in the opening segment of David Lynch’s neo-noir psychosexual fantasia Blue Velvet (1986). Both films signal the entry point into the world about to be inhabited, much like Alice falling down the rabbit hole and entering Wonderland.

Un Chien Andalou relied on the subversion of the real world rather than flight from it. Where other films of the time were more abstract, interested primarily in photographic effects and the manipulation of light and shadow, Buñuel and Dalí’s dissolved one easily recognizable image into another at high speed. At one point, the camera focuses on a hand swarming with ants. In quick succession, the image then dissolves into one of the armpit hair of a girl lying on a beach, the spines of a sea-urchin, and the head of another girl. In another sequence, the man caresses a girl’s breasts, which turn into her thighs while he is touching them. As once Buñuel once said:

The plot is the result of a conscious psychic automatism, and, to that extent, does not attempt to recount a dream, although it profits by a mechanism, analogous to that of dreams. The sources from which the film draws inspiration are those of poetry, freed from the ballast of reason and tradition. Its aim is to provoke in the spectator instinctive reactions of attraction and repulsion.

Buñuel’s intentions for Un Chien Andalou, like many of his films, was to disrupt the social order, especially to offend the intellectual bourgeois of his youth. He took this mentality into the premiere of the film, attended by elite members of Parisian society known as ‘le tout-Paris,’ in which he alleged he placed rocks in his pockets. If the event was a disaster, he would throw them. Fortunately for all, it was a success.

Buñuel continued this mission of offence and mischief in 1972’s The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie. Co-written with the French novelist Jean-Claude Carrière, the film weaves several linked vignettes in which a party of middle class attendees attempt, unsuccessfully, to dine together, and the interruptions that ensue. While Un Chien Andalou was intended to shock the bourgeois, The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie unpacks this section of society to reveal their entitlement, but also their fears. The film is a Surrealist comedy, and as the audience we are both in on the joke, and soon revealed to be part of the punchline, too.

Dinner parties are, society would have us believe, ordered affairs, but the Surrealists understood the absurdity of formal and stuffy dining. As children, we are conditioned ‘not to play with our food,’ yet food and Surrealism have a long history of play. In Daisies (1966), Czech filmmaker Věra Chytilová’s Surrealistic comedy about two young women revelling in strange pranks, a hilarious food fight ensues. One artist deeply involved in the social disruption of food was the Swiss sculptor Meret Oppenheim. In her defining book about women artists and Surrealism, Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement, Whitney Chadwick writes that Oppenheim’s ‘youth and beauty, her free spirit and uninhibited behaviour, her precarious walks on the ledges of high buildings, and the “surrealist” food she concocted from marzipan in her studio, all contributed to the creation of an image of the Surrealist woman as beautiful, independent, and creative.’ At the 1959 International Surrealist Exposition, Oppenheim presented Le Festin or ‘Cannibal Feast,’ a live art installation where a nude female model was used as a table to present a meal to attendees and partygoers. The photographer William Klein captured the image, which is more glamorous than gluttonous, and more gorgeous than grotesque.

Oppenheim was a sculptor with a knack for inverting the domestic. She covered a cup and saucer in fur and placed a trussed-up pair of virginal white shoes on a platter in the manner of a spatchcock chicken. Buñuel had previously played with dining in The Exterminating Angel (1962), a feature in which guests who have attended a lavish dinner party find themselves unable to leave following the room after their meal, resulting in all manner of chaos. Chaos is an element of L’Age d’Or, where Buñuel pushes the sexual proclivities of society, religion, and hypocrisy surrounding sex in high society. Once again co-written with Dalí, and cited as one of the first French sound films, in the film’s programme notes Dalí wrote that the idea ‘was to present the pure straight line of the conduct of one who pursued love in spite of the ignoble and patriotic ideals and other miserable mechanisms of reality.’

L’Age d’Or could be perceived as a Surrealist tale of desire between Gaston Modot’s unnamed man and his lady love Lya Lys, of the Amour Fou or ‘Mad Love’ that Breton talked about in his 1928 novel Nadja. The lovers are surrounded by the restrictions and constantly sneaking away to free themselves of these trappings and constraints, but everywhere they go, they are reprimanded for disturbing the proceedings.

The film begins like a nature documentary about scorpions, a veiled metaphor for aggression and torture while involving the Surrealist’s fascination with entomology, before continuing as a series of vignettes in which the couple’s romance is continually interrupted by everyone and anyone in their path, notably their family, society, and the church. In an early scene, a begraddgled man (one of a group of bandits led by the Surrealist artist Max Ernst) encounters a group of chanting Bishops (called the Majorcans or Mallorcans) sitting on a pile of rocks.

We later see the Bishops reduced to their skeletal remains, and witness a scuffle during the blessing of a Holy relic (what appears to be a concrete square). The spectacle, like most of L’Age d’Or, is as disruptive and darkly comic as it is blasphemous.

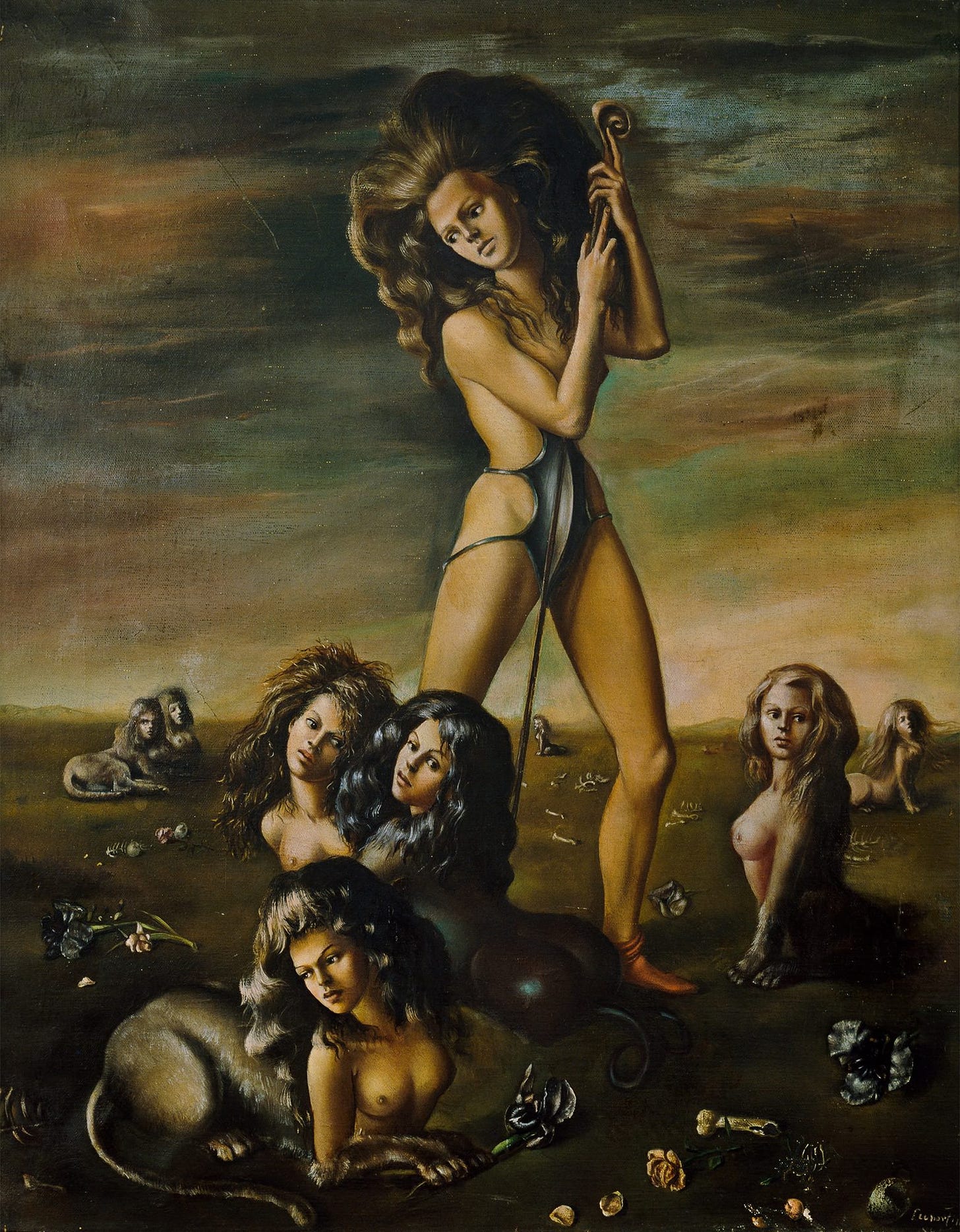

The farcical nature of this scene feeds into both Buñuel and Surrealist artists’ perceptions of religion. There is a lovely anecdote about the artist Leonor Fini arriving at one of the Paris cafés where the Surrealist group held regular meetings wearing pink silk cardinal’s stockings (items she had purchased from a religious vestment shop in Rome’s Piazza al Minerva). Breton was obviously thrilled at Fini’s anti-clericalism and display of cross-dressing. Yet this reaction was not her intention. Fini — a painter, set designer, illustrator, author, and costume designer who never wanted to be labelled a Surrealist despite her continued association — never wore the outfit with Breton in mind; her reason for wearing the stockings was much simpler: she liked the colour. She loved the erotic frisson experienced while wearing these stockings. She often wore scarlet cardinal robes for the same reason, and, as we know, she had been experimenting with clothing since childhood. Fini recounted this tale to the art scholar Chadwick in the 1980s, saying “I loved the sacrilegious nature of dressing as a priest who would never know a woman’s body.”

The note of pleasure ties into the sexual themes of L’Age d’Or. For example, fingers are frequently seen bandaged, but, as author Robert Short notes in his book ‘The Age of Gold: Surrealist Cinema’, that ‘fingers are bandaged because “bander” also means “to feel randy”. The girl’s ring finger bandaged alternates with the same unbandaged: horniness with detumescence.’ Self-pleasure, and pleasure, are evident throughout the film. In one scene, when her lover is called to a telephone call, the woman fellates the big toe of a statue until he returns in a bid to appease her lust.

The final vignette of L’Age d’Or doesn’t feature the lovers, but centres on The 120 Days of Sodom, the Marquis de Sade’s notorious pornographic and erotic 1785 novel about four libertines in search of the ultimate sexual gratification. Retreating to an inaccessible castle in Gemany for four months and locking themselves away with their accomplices and victims, four madams and 36 male and female teenagers, the orgies soon give way to abuse, torture, and death. In many ways L’Age d’Or, especially this final scene, can be viewed as a precursor — or prequel of sorts — to Pier Paolo Pasolini’s infamous 1975 interpretation of the book, Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom. Buñuel is not necessarily as graphic in his depictions, but he hints, and by continuing to push social and sexual boundaries, he concludes L’Age d’Or open to interpretation. This is affecting, and allows the viewer to chew on what has occurred, or what they believe has occurred, while leaving room for others to push the parameters further.Despite the controversial subject matter, Buñuel hoped L’Age d’Or would open to commercial audiences at the cinema on the Champs Elysées. Still, much to his chagrin, the film’s public premiere was at the smaller artistic Studio 28, with the Surrealists’ private screening at the Cinema du Panthéon. This downscaling of the venue, plus the film’s themes, saw the picture banned after six days of public viewing. Only three months earlier, in July 1930, Buñuel had told a Spanish journalist that he ‘wanted a moral scandal, that will consist in revolutionising the bad habits of a society in open conflict with nature’. It appears he had got his wish.

* This piece originally appeared in Radiance Films Dirty Arthouse Vol 2 (21 August 2023). Please click the link to buy.

From championing of a young artist named Jackson Pollack to the International galleries bearing her name, Peggy Guggenheim’s name is synonymous with art. Despite no formal training she possessed an artistic sixth sense when it came to greatness and an ability to seek out the marvellous. In Peggy Guggenheim: Art Addict, Lisa Immordino Vreeland weaves archive and audio recordings, film footage, and photographs with input from historians, curators and authors to produce an incredibly absorbing documentary on a remarkable woman.

From championing of a young artist named Jackson Pollack to the International galleries bearing her name, Peggy Guggenheim’s name is synonymous with art. Despite no formal training she possessed an artistic sixth sense when it came to greatness and an ability to seek out the marvellous. In Peggy Guggenheim: Art Addict, Lisa Immordino Vreeland weaves archive and audio recordings, film footage, and photographs with input from historians, curators and authors to produce an incredibly absorbing documentary on a remarkable woman.